News

Reviving the Rawi tradition: How AlUla’s contemporary narrators make ancient inscriptions accessible

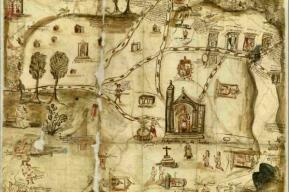

Spanning mountain walls and rocks over multiple heritage sites across Saudi Arabia’s north-western region of AlUla are thousands of inscriptions in Dadanite, Nabataean and early Arabic scripts. These collections of documentary heritage—which are being preserved and made accessible as part of the UNESCO Memory of the World (MoW) Programme—attest to the histories of the region, exhibiting that AlUla was an ancient bustling hub that attracted merchants, pilgrims and travellers from distant regions.

For epigraphists and experts, AlUla’s documentary heritage provides an illuminating view of social and economic practices of historical societies in AlUla, with references to religious rituals and agricultural practices found in engravings. But to ordinary visitors, AlUla’s inscriptions appear as undecipherable alphabets from ancient civilizations.

Within this gulf of understanding, contemporary Rawis have been bridging the gap of accessibility to documentary heritage and enabling intercultural dialogue by serving as translators, guides, cultural ambassadors and narrators for visitors to AlUla.

As part of the Royal Commission for AlUla’s (RCU) comprehensive regeneration project in the region, its Rawi programme provides opportunities for young people from the local AlUla community to receive training and employment as Rawis.

One such Rawi is Mamdouh Albalawi, who recalls visiting heritage sites as a child, unaware of the meaning of the inscriptions they displayed but inherently conscious that they possessed value. He remarks that he knew little about their meaning other than tales regarding the inscriptions, but says that “over time, as the artefacts became more unearthed and more studied, their significance became more apparent.”

Albalawi expresses his pleasure that “so many people from different countries across the world come to specifically visit these sites and to learn about our culture,” emphasizing that “I am very proud to be part of the team presenting this knowledge to visitors.”

While historically Rawis have perpetuated Arabic literature and poetry through oral traditions, memorizing and publicly reciting learned verses that would go on to be passed down and preserved over generations and centuries, today’s Rawis acquire a meticulously well-informed understanding of documentary heritage and its significance through dynamic courses, conveying knowledge to visitors and, in doing so, take charge of their cultural narrative.

To ensure the narrative of AlUla’s heritage is told by those who have served as its custodians over centuries, 75% of the RCU’s Rawis are from the three oases of AlUla, Khaybar and Tayma. Additionally, 56% of all Rawis are female, while 66% of Rawi department’s ‘stream leaders’ are female.

As the documentary heritage of AlUla is being further researched and understood in ongoing study, Rawis work closely with leading scholars to ensure the knowledge they convey is accurate and up to date, enabling them to fill any gaps of understanding from those visiting AlUla.

“We take information from scholars and transfer it to the visitors, in a storytelling way,” says Albalawi. He points to a Nabataean tomb’s façade marked by ancient inscriptions and illustrates that “this tomb belonged to Kam Kama bint Wa’ela, she wrote her name and her mother’s name.” The exclusion of her father’s name leads Albalawi to wonder whether she may have been an early feminist.

In embodying the past tradition of narrators while blending the custom with translations, expert understanding and a reinterpretation of the meaning of the past in view of aspirations for the future, the contemporary function of AlUla’s Rawis enables a unique form of intercultural dialogue. While documentary heritage belongs to and should be accessed by all, Rawis symbolize the MoW Programme’s recognition that local communities have served as guardians of a culture’s heritage over the years, and the Programme’s commitment to ensuring that community engagement is at the heart of preservation and access.

Memory of the World

The Memory of the World (MoW) Programme is a UNESCO initiative to safeguard the world’s documentary heritage and audiovisual heritage against collective amnesia. By facilitating preservation and access to the records of our history, the MoW Programme seeks to hone intercultural understanding and appreciation of our shared humanity.