These findings are part of a study undertaken for the UNESCO Science Report (2021), in which UNESCO tasked Science Metrix with collecting data on global publishing trends for 56 broad research topics of particular relevance to the Sustainable Development Goals, including that of tackling invasive alien species.

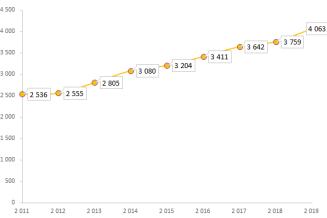

The study found that there had been a 68% increase in global publications on the topic of tackling invasive alien species between 2011 and 2019, from 2 536 to 4 063 publications (see figure). However, this progress stemmed from a modest baseline.

The modest scientific output on this topic translates into a blind spot when it comes to monitoring progress towards Aichi Biodiversity Target 9, which seeks to ‘eliminate, minimize, reduce and or mitigate the impacts of invasive alien species on biodiversity and ecosystem services’. According to the Convention on Biological Diversity, only 23 out of 196 countries (12%) are on track to meet this target and more than half of countries (114) are not reporting on their progress at all.

This is despite the fact that invasive alien species are a growing dilemma, according to a report released on 4 September by the Intergovernmental Science–Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), of which UNESCO is an institutional partner. The IPBES’ Assessment Report on Invasive Alien Species and their Control finds that the annual cost of invasive alien species has quadrupled every decade since 1970 to the point where it now amounts to US$ 423 billion.

Invasive alien species can outcompete native species. The IPBES report estimates that invasives have played a key role in 60% of the extinctions of plant and animal species around the world.

Invasive alien species can be devastating. They can bring disease, undermine food and water security and damage livelihoods. Dengue fever, Chikungunya and Zika are borne by the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus), for instance, which has managed to extend its range to northern France, thanks to milder winters as a consequence of climate change. The West Nile Virus is the leading cause of mosquito-borne disease in the United States of America.

Areas with a high ratio of endemic species, such as the Socotra Archipelago in Yemen, a UNESCO biosphere reserve and World Heritage site, are particularly vulnerable to invasive aliens. First observed in the archipelago in 2019, the invasive red palm weevil (Rhynchophorus ferrugineus), poses a real threat to local livelihoods, since date palms have traditionally been Socotrans’ primary source of food after milk and meat and their main agricultural output. Weevil populations can be controlled by the removal of infested palm trees, the widespread trapping of adult weevils, the targeted use of insecticides and the introduction of the weevil’s natural enemies, including different species of fungi. However, Yemeni scientists published just three articles in international, indexed journals between 2011 and 2019 on the topic of tackling invasive alien species.

The IPBES report estimates that more than 37 000 alien species are established worldwide. Of these, more than 2,300 are found on lands under the stewardship of Indigenous Peoples, threatening their quality of life and even their cultural identities.

Figure 1: Volume of global publications on tackling invasive species, 2011-2019

UNESCO Science Report (2021); data sourced from Scopus (Elsevier) by Science-Metrix.

High-income countries dominate research on invasive alien species

Invasive alien species pose a growing dilemma for countries of all income levels. Although low- and middle-income countries are publishing more than before on tackling these unwelcome guests, the topic remains dominated by high-income countries, which accounted for 80% of global output in 2019 (see figure). The fastest growth has been in lower middle-income countries such as India and Indonesia.

Most of the countries with the greatest output on this topic over 2016–2019 were high-income countries: the USA (4 991 publications), China (1 463), Australia (1 287), the United Kingdom (1 124), Canada (982), Germany (926), Italy (919), France (861), Spain (841), South Africa (775), Brazil (742), Poland (430) and the Russian Federation (420).

Among these leading countries, the most spectacular increases concerned South Africa (451 publications over 2012–2015), China (856), the United Kingdom (801), Poland (239) and the Russian Federation (180).

Figure 2: Contribution by income group to global publishing on tackling invasive species, 2011 and 2019 (%)

UNESCO Science Report (2021); data sourced from Scopus (Elsevier), including Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences; data treatment by Science-Metrix.

Among countries with at least 100 publications on this topic over 2012–2019, Indonesia ranked first for growth rate with 29 (2012–2015) and 73 (2016–2019) publications. However, this surge only translated into half the global average proportion of scientific publications on this topic (0.47). Moreover, this surge in output was visible across the board for Indonesia, which had decided in 2017 to link a scientist’s career evaluation to the size of their output in international, indexed journals.

Similarly, even though India almost doubled its output on tackling invasive alien species over the twin periods from 151 (2012–2015) to 273 (2016–2019), this corresponded to just 0.26 of the global average proportion of publications on this topic, suggesting that India is not specializing in this area.

Countries tackling invasive alien species

One of the highest rates of specialization (4.67) can be seen in Argentina: 279 (2012–2015) and 353 (2016–2019) publications. Another country displaying a much higher than average specialization (Specialization Index of over 1) is New Zealand (3.75). In 2016, the government launched the Predator-Free 2050 New Zealand initiative with the aim of removing five non-native predators: rats, stoats, ferrets, weasels and possums by 2050, in order to restore native biodiversity.

In 2018, the government pledged NZ$ 81.28 million over a four-year period to curb the influence of introduced species that pose a threat to endemic species and priority ecosystems. The Predator-Free 2050 New Zealand initiative is backed by research on invasive alien species that saw scientific output on this topic surge from 386 (2012–2015) to 501 (2016–2019) publications.

Another country witnessing a surge in research into tackling invasive species is Botswana, its output having climbed from 1 (2012–2015) to 15 (2016–2019) publications. A single invasive water fern, Salvinia molesta, was threatening the Okavango Delta, a UNESCO World Heritage site that contains Africa’s largest wetland. By introducing a Salvinia-munching weevil in 2002, scientists had managed to bring the invasion under control by 2016.

Invasive alien species threaten the livelihoods in 70% of African countries, as well as their food and water security. Water hyacinth has been a thorn in Kenya’s side for decades. Capable of doubling its biomass in just 15 days, thanks to the lack of natural predators and other favourable conditions, this invasive weed has resisted all attempts to eliminate it from Lake Victoria. The weed is wreaking havoc with the city of Kisumu’s water supply systems, river transport and fishing industry, and could ultimately threaten food security by blocking access to fishing grounds. As the vegetation mats block sunlight from penetrating into the lake, the weed also threatens plant and animal life. By preventing water flow, it also creates an ideal breeding ground for mosquitoes and other insects.

The local population has come up with some ingenious ideas to make use of the abundant weed, such as by turning it into biofuel or using the robust weed to make a wide variety of products that include rope, bags, pulp, cards, lampshades, furniture, baskets, footwear, animal fodder and biogas.

Kenya’s scientific output on tackling invasive alien species has more than doubled, from 30 (2012–2015) to 71 (2016–2019) publications. The country is devoting more than three times the global average proportion (3.48) to research on this topic.

Not enough measures in place to tackle invasives

The IPBES’ Assessment Report on Invasive Alien Species and their Control points to the generally insufficient measures in place to tackle the challenges posed by invasive alien species. Although 80% of countries have targets related to managing invasive alien species in their national biodiversity plans, only 17% have national laws or regulations specifically addressing these issues. Almost half (45%) of countries are not investing in the management of biological invasions.

We shall have to remedy this situation, if we are to meet the sixth target of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework adopted in December 2022, which seeks to reduce the rates of introduction and establishment of other known or potential invasive alien species by at least 50% by 2030 and to eradicate or control invasive alien species, especially in priority sites, such as islands.

Since regular monitoring will be crucial to measure the pace of implementation of the Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, UNESCO is setting up a database to enable people to follow the evolution of socio-ecological indicators and visualize land use changes in UNESCO’s network of designated sites.

Contact

For more information, please contact Susan Schneegans